The Long (Baltic) March

January - May 1945

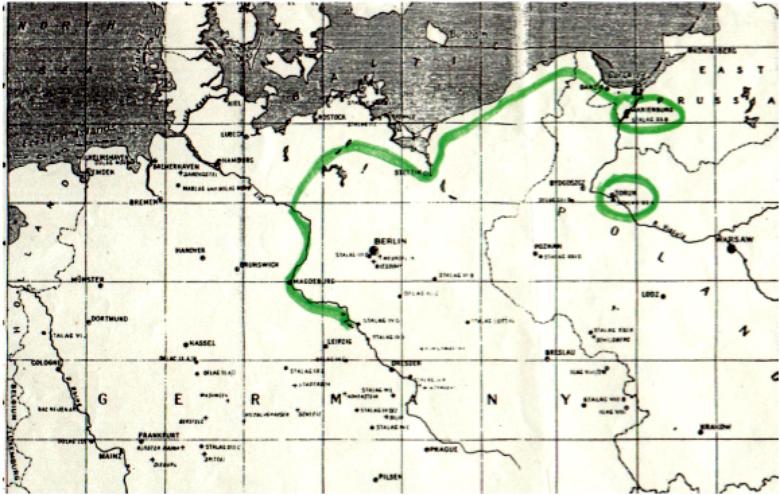

Danzic - Stolp - Koslin - Stettin - Swinemunde - Wisman - Wittenburg - Magdeburg - Halbe.

1,000 Miles (confirmed by the National POW Association).

“Sir,

I wish to make a statement in support of D.H. Bryant’s claim that not only has his medical complaint been aggravated by war service, but is actually attributable to it.

I was with Mr. Bryant during the period of his five years of prisoner of war life, and I was able to see the changes that the privation of this life brought upon him…

Then came the march known I believe in England as the “Death March” from East Prussia across the Polish Corridor ending in Halle, a distance of over 850 miles. I was with Mr. Bryant all this time, over three months of marching through the very bitter winter, when a carrot or a raw potato was a meal... “ - Henry Owens

In early January 1945, as the Russians made advances from the Vistula, the Germans decided to withdraw the POWs from the camps. The allies were destroying communications, and the Germans decided to force us out on the march again.

It was pitch dark when we assembled outside the gas works at Elbing, after our guard had warned us that “You are now back in the Front Line, any attempt to escape and you will be shot!” Snow had been falling all day; it must have been at least six inches deep. It was still snowing, and there was a bitterly cold wind, the temperature was well below freezing, around minus 30 degrees Celsius.

Over the years as POWs, we had accumulated extra clothing etc. from parcels sent to us through the Red Cross. We had hurriedly to decide what to leave and what to take, as everything had to be carried by hand. Preference was of course given to the small, built up stock of tinned food and powdered milk. I still had my army kitbag, so I put as much in this as I could carry. As we entered the main road in Elbing, there was evidence of the Russians‟ penetration, bodies lay about in the snow, and German troops dressed in all-white uniforms and heavily armed were moving east past us. It would appear that the Russians had attacked under cover of darkness, shot up the town, and retreated again.

We rendezvoused with other British POWs who had been in prison camps in the Elbing area, and were marched out, apparently making for the Baltic Coast. After marching for some time, we came across a long column of civilian refugees, who had been travelling in high-sided horse drawn wagons loaded with all theirworldly possessions. The column was at a standstill. Apparently they were held up because the crossing over the river Vistula was for the use of military traffic only. How long they had been there I do not know, but many had frozen to death still in their wagons, other bodies lay at the side of the road. They looked like wax dummies. We helped ourselves to any food we could find in these wagons, and marched on and crossed the Vistula towards Danzig.

It was on this section of the march that I faltered. I felt terribly tired, with a sinking feeling, as if the cold had affected my stomach. I sat on one of the abandoned carts and rested. Darky Bryant and other comrades pleaded with me to carry on, otherwise I would freeze to death or be shot. After a short while I recovered my strength, and from that moment, I did not falter for the rest of the march.

We marched nearly all of the first night, eventually stopping at a barn, where we lit fires and melted snow in our dixies, adding milk (klim) to provide a hot drink (no rations were provided by the Germans). The next day we marched on again, with the sound of Russian artillery in the background. As the packs on our backs were too heavy, most of us used makeshift sledges to pull our possessions along. As the days went by we got weaker; the built-up stock of food reserves had gone, we were plagued with lice and dysentery, and frostbitten limbs turned gangrenous. We were sometimes bundled into barns at night, but on at least one occasion we spent the night in an open field with no food at all.

It was not only British POWs on the march. It seemed that the whole of the civilian population of the Baltic States and East Prussia were fleeing from the Russians, some no doubt collaborators who feared for their lives. There were also Russian, French, and POWs of other nationalities. This all added to the food problem. Rationing had obviously broken down, and the Germans could not provide for themselves, even less for the refugees and POWs, these were low priorities. It was tragic to see POWs who had survived the horrific march into captivity from Dunkirk and St. Valery four and a half years previously, going down with dysentery, gangrene, and frostbite, and having to be left behind to die or be shot. There was no backup transport to take away the sick; you just left them behind, hoping they would survive, perhaps in a Russian hospital.

Route of 1000 mile March

show infoDescription:

The marking (green) shows the route taken my Henry Owens during the forced 1000 mile march of January - May 1945.

Credit:

Thanks to Robert Owens (son of Henry Owens)

Tags:

We marched twenty to thirty kilometres a day, with the sound of Russian artillery to our rear. Sometimes we rested for a whole day, and tried to tend our feet and other problems, but there was no remedy for worn out boots. Many carried on the march with rags bound around their feet, and my pal Darky ended the march with a pair of rope sandals.

When we rested for the night in barns etc., we never took off our boots, because we would get them stolen, or our feet would have swollen that much, we would not get them on again.

As far as food went, we only received one hot meal in the four months of our journey. That was beans, which gave most of us the runs. The Germans did, infrequently, give us some black bread and ersatz coffee, but most of the time we lived off our wits, stealing from farms, begging, or offering to supply a note saying that the donor had helped an allied POW with food so that the Russians would not harm them. It worked sometimes.

As the snow melted, our sledges became useless, and we had to go back to carrying our belongings by hand. This proved too much, and the roads became littered with discarded property, to begin with, extra clothing, then, as we got weaker, and the weather improved, even our greatcoats (God help us if it had turned cold again).

To add to our problems, as the allies and Russians advanced, the area between them got less, and bombing by the Russian and Allied forces became more concentrated. We were ever ready to dive into a ditch or a field to avoid unwelcome attention: we were on the receiving end when the RAF bombed Magdeburg, but luckily survived. I am reminded by my pal Darky of the time that the guards marched us into a wood stacked high with bombs and shells, about four feet high on either side.

We thought this is it; they are going to blow us up. To our relief, we marched out the other side.

The guards suffered along with us, but they seemed to have access to some food, and were changed at intervals. They became very touchy as it became obvious that the war was lost. You had to be careful of what you said, as some of the more pro-Nazi became trigger-happy. The Hitler Youth were also a worrying factor, as they rode around the streets of the towns firing their rifles. You felt that at any minute you could get a bullet in the back.

We were halted for a day at a big crossroads while German officers had a conference, we were then split up and marched into a wood where there were front-line German troops. They asked “Where are you going, Nach England?” (To England). It was only then we realised our ordeal was nearly over. We were billeted that night in a small village. I think it was Bitterfeld, north of Halle. We were given a meal of boiled potatoes, black bread, and coffee. The next day, to our surprise, a sole American rode into the village in a jeep. We rushed past our guards to welcome him, he told us to sit tight until the next day, when the guards would march us to the American lines. The following day we saw the guards lined up and shaking hands with each other, it seemed that the Americans had ordered that only so many should accompany us, the rest had the option of fighting the Russians, or surrendering to them.

After a short march we joined up with the Americans, who helped us across a blown up bridge, and eventually housed us in a former Luftwaffe barracks near Halle. They treated us like kings, but unfortunately the food was too rich for us, and we had to take it slowly.

A few days later, we were flown in American Dakotas to Brussels, examined, deloused, and supplied with new uniforms. Shortly after that we were flown in the bomb bay of a Lancaster bomber, to Sevenoaks in Kent. We were X-rayed, examined again, and sent on leave. This was 12th May 1945, almost five years since we had been taken prisoner.